So you want to be an entrepreneur: What they never tell you when you start out

The standard narrative of the entrepreneurial career looks something like this:

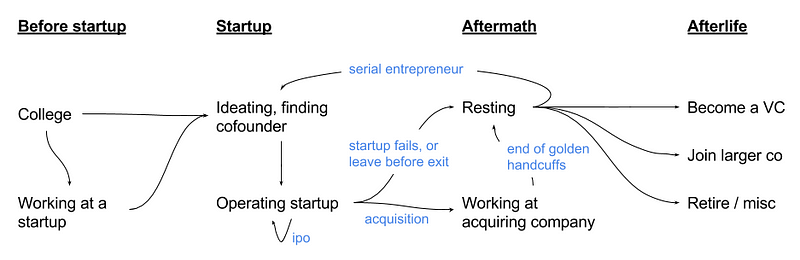

Like all fairy tale narratives, this arc is an oversimplification. Here is a more accurate map:

It can be hard to think about the big picture while you're in the midst of building a startup. After all, that first graphic is so much simpler than the second one. Startup life is also so tough that it's difficult to reason beyond the horizon of a single startup, and most advice out there is based around the mechanics of building a single startup versus building entrepreneurial careers. But by understanding the realistic outcomes, you're more likely to make better long-term decisions.

The idea that you can sell a startup and then 'live happily ever after' post-acquisition, in particular, is a dangerous myth.

Here's why:

'Live happily ever after' encourages lower standards for your idea. If exits are the ultimate path to success, then it's enough just to sell your startup, which is far easier than building a lasting, at-scale company. But careers are long, exits aren't magical outcomes for happiness and building for the longer term will offer more return on your work. Let's say that instead, you take more time upfront to find an idea that you're deeply passionate about. That passion will result in more drive to work on it over the long term, increasing the chances of success. You'll be more fully engaged, and willing to put in the intense levels of energy to achieve product-market success.

When things do start working, because you've been focused on building a long-term company you will have made solid foundational decisions that will let you build upwards for the decade to follow.

Working for the acquirers will have its own set of challenges. The acquisition process is a honeymoon period. Everyone's excited and making promises about how awesome it's going to be. Sometimes it is. But sometimes you're faced with a whole new set of problems. How do you merge disparate cultures, especially when you're the smaller group of newcomers? What's going to happen to the product and customers? You may not be able to move as quickly. It can definitely make sense to be acquired, and most successful exits today are acquisitions, but it's important to be aware that selling your company will bring its own set of challenges.

After leaving your startup or an acquirer, you won't be happy doing nothing forever. You should definitely take time off, and the first few weeks or months can be deeply relaxing. But believe it or not, you won't want to sit on a beach all day for the rest of your life. As Paul Graham says, dessert is appetising, but we're not meant to live off sugar. Infinite vacation sounds awesome, but fundamentally humans are built to work.

Most people also underestimate how many non-financial benefits they get from having work in their lives, including growth, identity, confidence, purpose, structure, satisfaction and social contact. Like dessert, after a certain amount of vacation, you won't want more.

But let's imagine you exited your startup. What do you do after you're done sitting on a beach?

Typically founders choose from four options after leaving a startup adventure:

Join a larger company. Become a Venture Capitalist. Start another startup. Retire forever.

We've already covered how #4 is likely not the right choice, at least until late in life. Let's talk about the rest:

1A. Join a larger company as a top executive.

Sometimes these are hires into new organisations, and other times acquirers preserve an acquired company, leaving them operationally independent. For example, Zappos and Twitch are still autonomous, and these kinds of exits are becoming more common as acquirers realise the challenges of integrating startups into their corporate structures — as mentioned above. It's also a good option for making the deal sweet enough for startups to agree to be acquired and keep key people on board.

Some exits also include the founder taking over parts of a larger established organisation. Diane Greene would be an extreme example: after selling Bebop to Google for US$380million, she's now Google's senior vice president of enterprise and is doing amazing work. Jeff Bonforte, the CEO we hired into Xobni in 2008, is now running a multi-thousand person organisation at Yahoo.

These are still fairly rare, however, partly because there are so few senior executive roles at large companies in the Valley, and partly because few startups reach scales sufficiently large enough for their founders to acquire the skill sets of a senior exec.

1B. Join a larger company as a middle manager or individual contributor.

This is fairly common amongst founders whose startups don't achieve escape velocity. There are many companies who want to hire ex-founders because they're often highly motivated and talented. They also bring a spirit of innovation and disruption which can be an antidote to larger companies' inertia and bureaucracy. Founders joining larger companies get to bring their skills to a business which is already functioning, with revenue, customers, etc, which offers a lower pressure environment. Sometimes this is just a step towards preparing to start another startup, but perhaps more often it's a permanent downshift.

This might be a good time to say: when making career decisions, there are no universally right or wrong answers. Each person should make the best decision for them based on their own personal values and what they want at any given point in life.

2. Become a Venture Capitalist (VC).

Ben Horowitz is the go-to example of a founder-to-VC transition. After selling Opsware to Hewlett-Packard for US$1.2 billion and working at HP as an executive, he started Andreessen Horowitz. I imagine it's a lot of fun to help the next generation of entrepreneurs succeed, largely by helping them avoid many of the hundreds of mistakes you made as an entrepreneur.

The big asterisk in this choice is that the day-to-day of an investor is quite different from that of a startup founder. While startup founders are operating, making a hundred decisions a day, VCs green-light one or two investments a year. It's a different lifestyle; whether that's good or bad depends on what you want at any given stage of your career.

3. Start another company.

…The truly crazy sometimes want to do it again.

For me starting Kite after Xobni was a chance to recycle all the lessons I learned the hard way, and to take another shot at building an at-scale company.

While I admire those who start company after company, I think the preferred outcome is that you build a lasting company early on, and operate there for quite a while. It's more interesting having evolving types of challenges as you grow, instead of scaling 1 to 20 people over and over again. And with a larger company comes larger amounts of resources that you can use to leverage your skills and a long-term vision.

More about designing for the long term in our next post!

Left with the above options, what do most entrepreneurs do? I'd love to see statistics around the popularity of each of these options. My guess would be one-third each.

I'll repeat this again: there are no universally "best" answers on career paths. My hope is that by being aware of the big picture you can engage in longer term planning both for your career and your startup.

Conclusion

In summary, post-acquisition startup life is not a fairytale ending; after resting you'll still want work. Build your startups for the long term. Think broadly about your career and what you may want at various career stages.

This is the first post of a series I'm writing on the entrepreneurial career. As mentioned, our next post will be about designing your startup for the long term.

Article by entrepreneur and Kite founder Adam Smith, originally posted here.